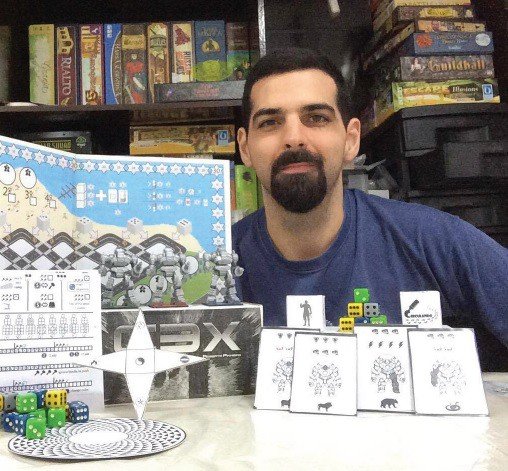

On February 3rd, 1986 was born in Recife — Pernambuco, Brazil, our interviewee today, Roberto Hugo Wanderley Pinheiro, better known in the Board Games world as Roberto Pinheiro: Game Designer, Event Organizer and an excellent player, currently residing in Juazeiro do Note, Ceará, Brazil.

What Makes a Game Designer for Board Games?

Roberto: He does the complete game creation arc in mechanical terms. He has the idea of the game, elaborates the mechanics, makes it playable through tests. In short, this is it. Of course, many Game Designers expand this scope and embrace more activities.

For example, it is quite common for Game Designers to also be the ones who develop the game. That is, they test, balance and test again, exhaustively. This is because most Publishers do not have people for this type of work, and it generally falls to the Game Designer.

On other occasions, the Game Designer even takes on the role of an artist, making the art of his game; Graphic Designer, assembling the fitting of this art inside the game; or even an art director, sending the demand to an artist, but in which he dictates the resulting product.

“So, a Game Designer is almost like a board game wildcard. It can “just” make the game systems or go much further than that.”

- Roberto Pinheiro

Is there some kind of rite for creating board games?

Roberto: I take three little jumps backwards in the ocean waves. Just kidding... It usually starts with a very abstract game idea. I write it down, and it matures little by little. It can be just a concept idea or an idea of mechanics or even a general flow of the game. All of this goes into a giant file that I use as a repository for these ideas.

Eventually, when I'm interested in creating a new game, I take a look at this repository, choose the one I like the most at the moment, and start the process.

How is the creative process?

Roberto: This seems to vary a lot from author to author. There's always the discussion “mechanics” or “theme” first... I'm more into mechanics, thinking of different ways to use something that already exists or simply mixing them up differently. With the more central mechanics kind of defined, I start trying to put a theme in the game, so it serves to support future decisions.

I think staying fully into the mechanics for too long is going to make the game very difficult to fit in the future when it's fully run. Not to mention that thinking about a suitable theme already provides some interesting decisions that facilitate the general development of the game.

“Once I have the game in mind, I try to devise the least viable game flow so that I can play a piece of the game or even a full game.”

- Roberto Pinheiro

With all this in the conceptual world, I build a prototype as soon as possible to test. If the game looks promising, I'll have several prototype versions as I tweak rules and often change the game on a large scale. At this stage, I test it myself, until the game is playable from start to finish. Right now, I have a playable prototype that I can present to other people.

This initial introduction is for friends or acquaintances only. Thus, I have a vision of a complete game match (or segment of it) being played by people other than me. This process can yield considerable changes and even discard the game entirely because some elements, when tested with other people, can generate some irremediable problems that I hadn't foreseen before. If everything is going well, the tendency is for the game to gradually evolve with each Playtest. In case it's fun, I put strangers to suffer this time to gather Feedback less biased through friendship's eyes.

All processes from the first prototype are very similar in the sense of repetition. If you want to create games, you will have to be willing to play your own game over and over again. Eventually, after playing a lot on your own, playing with friends and playing with strangers, you'll have several Playtests on your back and a good sense of how the game is doing.

“If you want to create games, you will have to be willing to play your own game over and over again”

- Roberto Pinheiro

At some point, you determine that as done. It's a very difficult part, as the tendency is to keep tweaking and improving indefinitely, but everything has to come to an end. When is this moment? For me, it's when people start getting random criticisms about art or graphic design or any other non-gameplay elements. That's when I realize that my game is good and as people can't criticize anymore, they end up finding other aspects to try to give some Feedback.

Do you have a defined style?

Roberto: I don't think so. Maybe the focus on mechanics? However, I try to create games of the most diverse styles and categories. I have games that take 2 hours and games that take 10 minutes. I have cooperative and competitive games. Furthermore, I have games set in medieval and futuristic times.

“Some Game Designers have a favorite style, but most live off cycles.”

- Roberto Pinheiro

Uwe Rosenberg (famous for Agricola) goes through cycles, once had a time of just creating simple Card Games, then went through Worker Placement and, more recently, created several games using polyominoes (those Tetris-style pieces).

So, I would say the same happens to me because when some mechanic or concept works, I end up creating more than one game on that line. Until a new idea or concept comes along and the style changes with it.

Do you research on the market's demands?

Roberto: Rarely. The Game Designer's role is to create a good game, not necessarily the best-selling game. Of course, if you want to publish your game on your own, it's good to study it well and see what the public's trends are at the moment. After all, you will invest money to produce the game, and you will need to sell it.

However, in case you are not going to publish your own game, this is a role for the Publisher. In this case, the Game Designer creates his game (or several games, preferably) and it is up to the Publisher to select the most suitable one. Among the selection criteria are market demands, product line and, of course, game quality.

What games have you released and which ones are on prototypes?

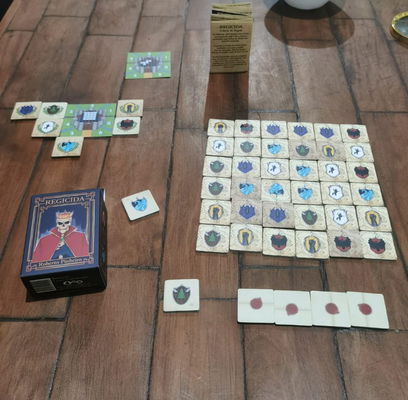

Roberto: I published a game independently, that is, I did the entire process from the game design to the product. It's a small game called Regicida, it's a bluff and deduction game that fits 1-6 players and a complete match lasts less than 25 minutes.

The general idea is that several Houses are vying for the throne, but nobody knows which player belongs to which house.

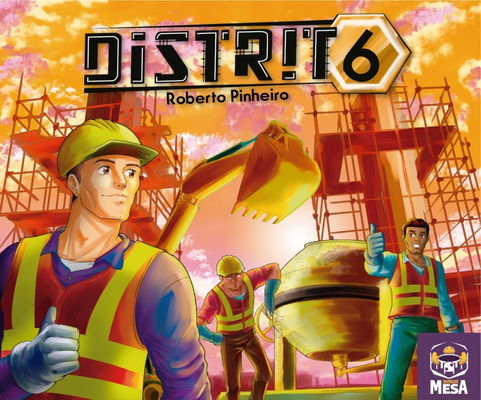

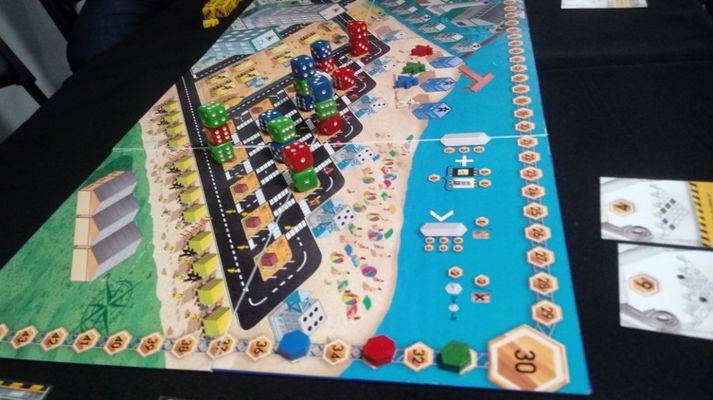

In addition to Regicida, I have a game due out this year by the publisher Vem Pra Mesa, it's called Distrito 6. It's already a much bigger game, that lasts around 90 minutes depending on how many people at the table, which can vary from 2 to 4 players.

It is a more strategic game of building cities using dice, but with low luck influence, like any good Euro Game.

As for prototypes, I have a plethora of them. Some I could highlight are:

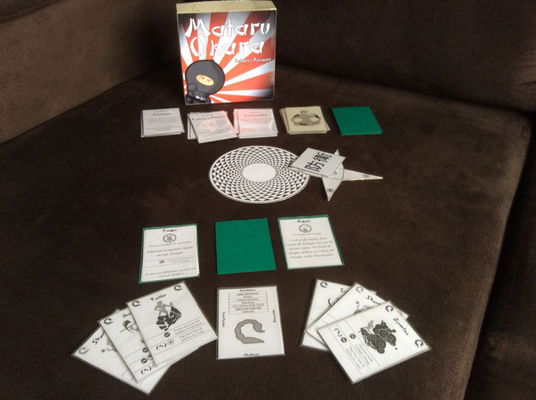

• Mataru Okara: a Dexterity game in which each player is a ninja who throws shurikens trying to gather the parts of an amulet and win the game;

• Teotihuacã, a strategic game with many dices in which each player tries to make the best pyramid;

• Alters, a game for up to 8 players in which each player represents a person's identity with multiple identities competing to take full control;

• Alien Alarm, a real-time cooperative game that is basically a Tetris but instead of giving the commands you want to perform (move, rotate, etc), you give the times you want the commands to occur (confusing, but interesting).

There have been more than 20 games on this journey, and you can check them out on my Portfolio, Facebook

or Instagram

.

Thanks for the invitation!

— Comentarios 0

, Reacciones 1

Se el primero en comentar